Have you ever heard someone call a book “elicious?

I think, to other fiction-readers, this resonates.

But to people who don’t indulge in fiction, this may seem like a strange word to describe a book. To these people, I have one simple request: give yourself the chance (and importantly, the time) to immerse yourself in a work of fiction. Then see if the word fits.

Before we get into what happens when you do immerse yourself, let’s circle back to a word I just used: indulge.

Reading for pleasure is often considered indulging. And it seems, for that reason, we tend to shy away from the treat. Why?

The stigma against reading for pleasure

The way in which a society evolves, to some extent, shapes collective perspectives on everything.

In our fast-paced, high-stress society, “indulging” often has negative implications—perhaps we think about indulgent activities as a waste of time. Sometimes it seems like we think about reading for pleasure as something that we must earn the right to do once we’ve completed all “necessary” tasks.

But in reality, reading fiction is much more than just a self-indulgent pastime.

The rise of self-help books

As a child, I was an avid reader. No, really. I was the girl who, crossing the busy streets of Manhattan, was buried inside of a book. My mom would literally have to guide me across the street.

Of course, she could’ve exercised some kind of authoritative tactic (“if you don’t look up when you cross the street, you don’t get dessert tonight”), but really, what parent is going to go to lengths just to limit reading? Not mine. MIine instead settled for pulling me by the arm when I didn’t listen to the simple request to look up while crossing the street.

As I got older, I started noticing that the “Featured Books” section at Barnes & Noble increasingly held “self-help” and non-fiction guides, and fewer of those juicy fiction gems which I had come to love.

When I was reflecting, I was pretty sure that I wasn’t making this up, and that this surge did actually happen—but I wanted to make sure (and I was right!).

I actually did get into some of these books (maybe in part because of mere exposure?). Some of them had some interesting insights (shoutout Mark Manson!)—but often, I found that I could only make it about halfway through.

Reading fiction vs. non-fiction

Looking back, I realize that my headspace when reading non-fiction was completely different from when I was reading literary fiction.

With non-fiction books, I felt very aware of myself and my thoughts—which led to actively doing more reflection as I read. In addition, I felt like I was trying to extract clues and bits of information that would lead me to “answers.” And, as advertised, that’s what self-help books are supposed to do (provide you with answers and insights). Basically, I was on alert.

With fiction, as cliché as it sounds, the world did seem to “fall away.” And rather than being on a mission to gain something, I was just enjoying the story—and becoming immersed in the characters’ worlds.

…And the fall of fiction?

One of my favorite non-fiction books to this day has been Stolen Focus: Why You Can’t Pay Attention, by Johann Hari.

This self-help book dives into the way in which our society has collectively experienced a decline in our ability to focus, and how major forces related to social media and technology have played a contributing role.

But ironically, the part that piqued my interest was where Hari discusses how the amount of fiction we read has rapidly decreased over the past couple decades. And how the number of people who actually get through books that they start has also declined.

Hari made an excellent case in regards to how while reading non-fiction elevates our repertoire of knowledge and facts (and obviously can help us advance in our academic and professional lives), the benefits of reading fiction may be unmatched.

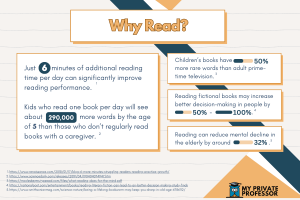

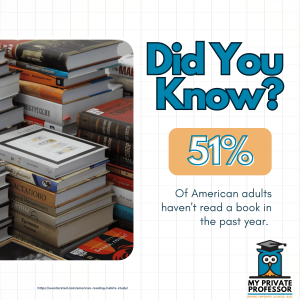

According to a 2021 Gallup poll, Americans are reading less than they have in over thirty years.

But specifically, we’re turning less to fiction, and more to non-fiction.

According to Publisher’s Weekly (which cited figures from the Association of American Publishers), fiction buyers fell by seventeen percent between 2013 and 2018.

Here’s the funny thing: Americans started gravitating toward these self-help books seemingly to better manage their anxieties (for nearly the past decade, depression has been on the rise). And sometimes, these books do help.

They provide valuable strategies to improve your life, anecdotes that allow you to feel as though someone else can relate to what you’re going through, and science-backed insights to help you live your best life.

But the truth of the matter is that completely foregoing fiction for non-fiction may not be in your best interest.

What happens inside the brain when you’re reading fiction?

If you’ve ever had the pleasure of becoming completely immersed in a book, you know that it’s a feeling (practically a trance) like no other.

Neuroscience has demonstrated that when you read fiction, something very cool happens inside your brain. And that there’s a reason for this trance-like feeling.

Reading fiction basically puts you in a simulation

In a 2021 study published in Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, researchers investigated what happens in the brain on fiction. The researchers used fMRI on self-described Game of Thrones fans to understand more about the link between fictional character-absorption and brain activity.

They found that, the more participants tended to strongly identify and become immersed with a fictional character, the more they used the part of their brain that they use to think about themselves, to think about the character.

Off the bat, this tells us that in general, fiction can affect how we think.

In a different study published in Brain Connectivity, researchers looked at the effects of reading fiction on brain activity. They found that reading a novel causes changes to the left temporal cortex, which is associated with understanding language. And, significantly, this region’s neurons are associated with “embodied cognition” (when the brain tricks you into thinking you’re doing something you’re not).

Reading fiction involves more than just reading…

As Stanford professor Natalie Phillips found, when you read fiction, you think through the protagonist’s actions, considering what you’d do in the same situation, or what you’ve done in the past. You practice, mentally, making decisions that have consequences.

In her study, Phillips demonstrated that blood flow increases not only to regions responsible for language processing, but to areas that have nothing to do with language. For instance, reading fiction activates your motor cortex (which is involved with physical movement), and areas related to sensory experiences. And this helps explain why, when you become immersed in a work of fiction, it’s like you’re in a simulation.

The experience is similar to, say, when you look at the PF Chang’s menu and see something that looks tasty, and begin to imagine yourself eating it (this is particularly noticeable if you’re really hungry!).

Or, if you read about Harry and Malfoy engaging in an intense duel, you might feel as though you’re right there in the ring with them.

So what’s happening is that essentially, your brain tricks you into thinking that what’s happening to the protagonist is happening to you.

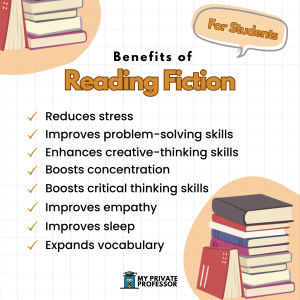

Reading fiction helps you be more empathetic

As a result of becoming immersed in a fictional world, you become more attuned to the characters’ thoughts, feelings, and ideas. And this allows you to gain more of a tolerance for empathy in real life.

In a 2006 study, researchers investigated this relationship, finding there was a direct, positive association between reading fiction and empathy levels (based on empathy tests).

A study done at The New School ( NYC) found that, indeed, reading fiction improves one’s ability to understand what others are thinking/feeling.

In the study, participants were given different reading assignments (literary fiction, non-fiction, genre fiction, or nothing). After they completed the assignment, they took a test measuring their ability to identify/understand others’ thoughts and feelings.

The researchers found that participants who read literary fiction had significantly higher empathy scores than participants who read non-fiction or nothing.

Evidently, expanding your capacity to understand the people on the page can actually seep into your real life!

Reading fiction reduces biased-based thinking

In novelist Elif Shafak’s Ted Talk, Shafak describes the dangers of shielding ourselves in “cultural cocoons.” She talks about the old Eastern tradition of covering up mirrors in the house, based on the knowledge that it’s unhealthy to spend too much time staring at your own reflection.

Essentially, staying surrounded by people like yourself leads to greater divisions. In turn we’re more likely to perpetuate and believe stereotypes.

Perhaps you’ve learned about how as humans, we innately hold biases—many of which lie in our unconscious (implicit biases). And of course, these biases come into play when we make judgments or conclusions about others.

Actively learning how to reduce these biases is directly related to increasing empathy. And as mentioned, reading fiction can help increase your capacity for empathy, a concept which is understandably difficult to grasp.

After all, isn’t it impossible to truly experience someone else’s emotions/feelings if you haven’t ever experienced them for yourself?

As it seems, reading fiction might be one of the closest avenues for achieving it.

The Harry Potter study

In the adored Harry Potter series, there are continual references to biases that parallel those in our world today. For instance, the perception that Mudbloods (wizards born to non-wizard parents) are inferior to pure-bloods (born to wizard parents).

A 2014 study took inspiration from the series to investigate the relationship between reading fiction and biased-thinking.

In the study, Italian students filled out a survey on their attitudes toward immigrants (a commonly stigmatized group in Italy). Those in the treatment group read passages dealing with prejudice/bias (for instance, when Malfoy calls Hermoione a “filthy little Mudblood”). Those in the control group read passages unrelated to prejudice.

The participants then re-answered questions about their view on immigrants. The students who read excerpts related to prejudice showed higher levels of empathy toward immigrants. Contrastingly, those in the control group didn’t show any significant attitude changes.

Dan Johnson’s study

In a similar study by Dan Johnson, participants read excerpts from Saffron Dreams, a novel about a Muslim woman living in America. Some participants read a 3,000-word except in which Muslim-American women were the object of racial prejudice. The other participants read synopsis of that excerpt, which maintained facts, but left out sensory imagery related to the character’s complexity.

Afterwards, participants were presented with faces of Arab-Caucasians, some of which appeared angry. The participants were then asked to identify the race of each person. Those who read the short synopsis were disproportionately likely to characterize the angry faces as Arab. Meanwhile, this bias was absent among those who read the long excerpt.

This tells us that reading and learning about different types of people can help reduce bias-fueled judgements and decisions.

Reading fiction promotes open-mindedness

In life, many people believe that open-minded = good, and close-minded = bad.

With an open mind, you can be a better listener and actively take into consideration different perspectives, solutions, and ideas. Having an open mind can thus benefit several areas of your life including academic performance, relationships, and goal-management skills.

In a 2013 study, researchers examined something called cognitive closure, which is the need to quickly reach a conclusion and the avoidance of ambiguity or multiple perspectives.

They found that those with a strong need for cognitive closure were less able to change their mind as information became available than those with less of a need for cognitive closure. Those in the former group were thus more strongly attached to their initial beliefs and less able to draw multiple conclusions.

What does this have to do with fiction?

Well, researchers at the University of Toronto found that people who read short stories—compared to those who read essays—had significantly less of a need for cognitive closure.

When you think about the nature of reading fiction, this makes sense. Non-fiction usually leads to some type of “answer”. But fiction invites us to mull over ideas and continually take in information that adds to the narrative.

Final thoughts

So if you’re ever feeling guilty about taking time to lose yourself in fictional worlds, think about the science-backed benefits. Think about how whenever you read fiction, you’re literally doing a brain workout—opening your mind and importantly, growing.