Over the past couple of decades, a heated debate around reading instruction methods has been brewing—as such, something called the science of reading has gained major attention.

But in the past couple of years, largely due to the pandemic-related learning losses students faced, the topic has majorly surfaced.

During the pandemic, reading scores had the greatest decline reported in thirty years.

But here’s the thing—reading scores had already been declining before the pandemic. Prior to COVID-19, almost two-thirds of U.S. students couldn’t read at grade level.

But seemingly, thanks to the pandemic (never thought I’d say that!), we’ve begun waking up to this issue—and recognizing how it’s symptomatic of more than just COVID-19.

What is the science of reading?

The science of reading is a large body of research on what’s most effective when it comes to teaching kids how to read, and scientific evidence on how children learn to read. Within this model, there are five key components:

- Phonological awareness

- Phonics

- Fluency

- Vocabulary

- Comprehension

However, despite the mass of research, which says that phonic-based instruction (focusing on sounding out words and connecting sounds to pronunciation and meaning) is a critical part of teaching reading, most U.S. schools use balanced literacy.

What is balanced literacy?

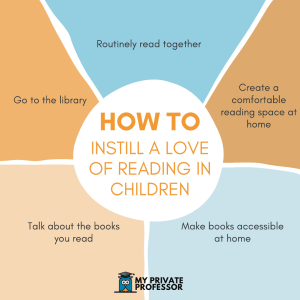

Balanced literacy focuses heavily on encouraging regular exposure to books. The specifics are usually unique to each teacher, but generally, balanced literacy methods combine various methods such as guided reading, reading aloud, and independent reading. And significantly, balanced literacy aims to promote a love of reading.

However, it turns out one of the major ideas behind balanced literacy is faulty.

Here’s what this idea is: That beginning readers don’t have to sound out words. That they can, but don’t have to, because they can rely on other cues. For instance, kids can look at elements like the pictures, the sentence structure, or the first letter of a word.

As noted, balanced literacy aims to promote a love of reading among students. And since using those cues above is less cognitively challenging, it’s unsurprisingly more enjoyable for students. But even if using this method is initially more enjoyable than actually sounding out the words, students often struggle majorly later.

This is because in reality, cue-based reading strategies can harm students by eliciting bad reading habits that are difficult to break and in turn impairing their reading skills. So in the long run, children who learn this way may not end up loving to read because they won’t fully be able to read!

While parents can supplement in-school instruction by reading to their children, it might not be enough. In the APM Reports Podcast, ”Sold a Story: How Teaching Kids to Read Went So Wrong,” host Emily Hanford suggests that there’s this belief that as long as parents read with them, kids will naturally learn how to read. And for some kids, this does happen. But research shows that up to sixty percent of kids need systematic, explicit instruction.

Marie Clay and the origin of cue-based reading instruction

To understand why so many schools haven’t been using instructional methods based on the science of reading, we have to go back to the 1970s and learn about a woman named Marie Clay.

While earning her doctorate in New Zealand, Clay was trying to understand how educators could support struggling readers. So she decided to conduct a study to understand what was happening with these readers.

Ultimately, Clay wanted to identify what determines a good reader. In Clay’s study, she observed one-hundred children during their first year of school. She analyzed students’ writing/reading behaviors in the classroom and assessed progress at three points during the year.

Clay concluded that when good readers come to a word they don’t know, they ask themselves critical questions to figure it out. She claimed that good readers don’t have to sound out words and don’t get stuck on letters.

Essentially, the study convinced Clay that the individual letters aren’t reliable cues. Rather, she theorized, good readers, to extract meaning “skim” words, and their last resort is to sound them out.

In 1976, Clay created a ‘Reading Recovery’ program to help struggling readers use strategies that she thought good readers were using (utilizing various cues). Within a few years, the program was all over New Zealand.

In 1984, professors in Columbus brought Clay’s program to Ohio. And by the end of the 1990s, the program was in more than one in five U.S. schools.

The thing is, Emily Hanford notes, Clay assumed that we’d never actually know what’s going on behind someone’s eyes when they’re reading. But in reality, scientists were starting to dive into just that.

Researchers proved Marie Clay’s theory wrong

In the ’70s and ’80s, scientists were utilizing newfound technology (brain scans, eye-tracking technology) to study the process of reading.

Eye-tracking studies found that good readers rely on the letters to read words. And experiments showed that a highly-developed reader could only predict around one in four words using contextual cues.

This negated Clay’s fundamental theory. Study after study demonstrated that good readers do, in fact, process every letter in every word.

Notably, research found that it was poor readers who were likely to rely on contextual cues. So this cue method, which rapidly became popular around the world, was promoting strategies based on the methods of struggling readers.

So why is it that we need this systematic instruction when it comes to reading? And how is it that, conversely, we naturally learn to speak?

Well, in a nutshell, we’re born with brains that are wired to speak, but not read.

We learn to communicate verbally by seeing and hearing the people around us speaking. But with reading, we have to learn that all these words they’ve learned make up smaller units of sound. And this, as science shows us, is often only achieved through explicit instruction.

As you connect the pronunciation of words to their meanings, you create new neural pathways, which allows you to store the words. And according to research, phonic-based instruction is a critical part of this process.

So, if we knew this in the 1990s, why have teachers continued to use Marie Clay’s methods?

Why cue-based reading remained in place

In 2001, George W. Bush’s Reading First proposal was passed, which aimed to improve reading instruction by implementing science-backed instruction.

Although the senate majorly supported the proposal, a lot of educators liked what they were already doing—so it would be difficult to implement new methods. On top of this, there were some pretty powerful people rallying to keep the current methods in place. Namely, Irene Fountas and Gay Su Pinnell.

Two major forces: Irene Fountas and Gay Su Pinnell

Irene Fountas and Gay Su Pinnell are professors and authors of widely-used educational materials. For decades, the two have advocated for cue-based reading instruction.

In 2001, Fountas and Pinnell (F&P) were promoting “guided reading,” which was a version of Marie Clay’s Reading Recovery program. By the early 2000s, guided reading was everywhere.

In guided reading, kids get (increasingly challenging) “leveled” books which contain pictures that correspond to words. Students go through the books on their own, and then discuss the meaning of the stories with the teacher. And this method is based on Clay’s theories that beginning readers don’t need to sound out words.

(F&P were huge supporters of Marie Clay. In fact, Pinnell was one of the professors who brought Clay’s programs to the U.S. in 1984!)

F&P were professors—so even if they didn’t back their methods with research, people trusted these women. Hanford explains that educators didn’t question F&P’s methods. The two had a huge following (which, when Hanford describes it, sounds almost cult-like).

Failure to implement Bush’s reading initiatives

F&P’s advocates wanted to hold onto their beliefs despite the research that told them to do otherwise. (Belief perseverance is the innate human tendency to maintain a belief even after discovering conflicting evidence.)

In August 2005, the Reading Recovery council of North America filed a complaint with the U.S. Department of Education, claiming that the department was spreading a misinformation campaign against Reading Recovery.

So the department conducted an investigation. The investigation found that some consultants who reviewed Reading First grant proposals had connections to commercial reading programs, which put Bush’s Reading First campaign under fire.

Evidently, Emily Hanford notes, the reading first program couldn’t withstand the controversy—by the end of 2007, democrats in congress cut the budget for Reading First by more than 60%. Within a few years, funding was eliminated.

Meanwhile, there was another major figure advocating for balanced literacy.

Who is Lucy Calkins, and how does she fit into the story?

Lucy Calkins, a professor at Columbia University, led an organization called the ‘Teachers College Reading and Writing Project,’ which aimed to advance certain methods for teaching reading.

Calkins, for decades, believed that children were natural readers. Her instructional methods focused on helping children to understand the meaning in stories.

Additionally, a major pillar behind Calkins’ curricula was the idea that, if you give children the motivation to read, they’ll be more likely to learn. And this requires giving them a lot of freedom and choice in what they read. Evidently, this aligns with one of the major goals of balanced reading—promoting a love of reading.

Calkins was not into teaching mechanics— she believed that spending too much on grammar and word construction was dangerous.

Notably, despite her lack of evidence that her methods were effective in teaching children to read, Calkins (like F&P) had a major following, and was basically a celebrity in the education world.

Another piece of the puzzle: Heinemann

Finally, another influential force in the reading battle was the publisher behind Calkins, Fuentes, & Pinnell. Welcome: Heinemann.

According to Hanford, in the early 2000s, Heinemann was publishing products based on Marie Clay’s theories, despite evidence that these products didn’t work well.

At the time, there was a growing demand for assessment systems to gauge student progress and for intervention programs for struggling readers. So Heinemann began publishing products to meet these demands.

One of them was called the Leveled Literacy Intervention (LLI), a program for teachers to use with small groups of children who were struggling to read (an F&P product based on Marie Clay’s theories).

In 2007, F&P published their benchmark assessment system, aiming to help teachers calculate students’ progress. This became a huge Heinemenn product.

According to Emily Hanford, among eighty-three districts, all but five bought Heinemann products in the last decade—and spent a LOT. For instance, New York City schools spent $21 million on Heinemann products (based on record requests).

Bottom line: Heinmann was a huge, powerful company, and the majority of U.S. schools have used its products.

Research on leveled books

Here’s the thing: kindergarteners and first-graders in the LLI program got better at reading leveled books. But according to a study at the University of Memphis, the program had no significant impact on their ability to sound out words.

That is, children were moving up to higher reading levels, but weren’t getting better at reading. And it’s this study that F&P and Heinemann point to as evidence that the program works!

In theory, reading levels are fantastic. It can be valuable to identify students by reading level and then have them work together. The problem, though, is not with reading levels, but with the leveled books.

The problem with leveled books

In the 1990s, Fountas and Pinnell had devised a benchmark system for monitoring student progress using leveled books.

But the system didn’t test students’ ability to sound out words. Rather, it tested how well they could read leveled books, which, at the lowest level, encouraged children to use pictures and cues to identify words.

And there’s an evident problem with this system:

Fountas and Pinnell explicitly claimed that educators can use their system for universal screening. But there was no empirical research or data confirming that the leveled reading systems were effective in doing so.

Recent research: why this topic continues to be relevant

In 1993, researcher Sandra Iverson conducted a study comparing Reading Recovery to a similar system that incorporated phonic-instruction. She aimed to determine if kids would do better in the latter condition.

Iverson found that students in the latter condition needed far fewer lessons to be successful at reading than those receiving original Reading Recovery. She also determined that kids could initially be successful in Reading Recovery without really knowing how to read. But later, they would either stay at the same level or move backwards.

In 2014, researcher and professor Matt Burns designed a study to determine whether F&P’s benchmark system could effectively identify struggling second- and third-grade students in Minnesota.

Burns used three assessment systems—one was F&P’s benchmark system, and the other two had been shown to help identify struggling readers. The study found that F&P’s assessment system had about fifty-four percent accuracy accuracy in diagnosing children who were struggling with reading.

According to Burns, there exist several assessments that can identify struggling readers—free assessments which take a few minutes. Meanwhile, the F&P’s benchmark assessment system takes twenty to thirty minutes per child and costs almost $500.

And there’s one more study that’s very important to this story.

This study, one of the largest studies of education intervention programs, began in 2011. It looked at thousands of kids to determine Reading Recovery’s effectiveness.

The researchers found that in first grade, kids in Reading Recovery performed better than kids who weren’t in the program. But the study didn’t end there.

Researchers monitored the students a few years later, finding that third- and fourth-graders who received Reading Recovery had lower test scores than students who didn’t have Reading Recovery. And those kids who had Reading Recovery in first grade had more reading interventions in second, third, and fourth grade than those who weren’t in the program.

What’s happening with Calkins, Fuentes, and Pinnell today?

Encouragingly, last year Lucy Calkins asserted that she and her colleagues decided that they needed to modify their curriculum and approach. She has since moved away from cue-based reading instructed and has implemented phonics into her curriculum.

As for Fuentes and Pinnell? When more research was emerging, they were quiet. In November 2021, they finally broke the silence. They published an audio Q&A series, in which they reaffirmed their commitment to Marie Clay and cue-based learning.

And finally, Heinemann.

In her podcast, Emily Hanford reports that she spoke with a representative at Heinemann, seeking to understand the publishing company’s stance. The Heinemann representative addressed the way in which their major authors (Calkins and F&P) were in disagreement.

The representative said that a difference in opinion, and debate, is good. But does this confront the blatant fact that there’s a huge amount of research saying that the methods of two of their influential authors (F&P) are ineffective and even harmful? Not so much.

Final thoughts

Ultimately, it seems, we all want kids to enjoy reading. And cue-based methods seem to achieve that goal—but only in the short term. Additionally, these methods may very well be easier and more convenient for adults.

Interestingly, Heimenan’s tagline was “dedicated to teachers.”

But if the goal is to improve reading skills in children, the process should be about the children, right?

It seems that thankfully, we’re starting to wake up.

Since 2019, at least twenty-six states have passed laws that call on schools to adopt instruction based on the science of reading, according to APM Reports.

Some more encouraging reading curriculum developments across the country:

- Mississippi was one of the first states to implement laws related to evidence-based reading instruction; in 2019, it was the first U.S. state to significantly improve fourth-grade reading scores.

- Colorado now requires districts to use a reading program based on the science of reading.

- Indiana recently partnered with the Lilly Endowment to implement instruction based on the science of reading.

- In April 2022, Virginia implemented new “evidence-based” teacher-training regulations.

And now it’s time to spread the word about the science of reading, and ultimately, continue empowering the next generations to become successful readers.