Throughout the past decade or so, the collective focus ability within the U.S. has been rapidly declining. Research shows that—shockingly—the average attention span is down from 12 seconds in 2000 to eight seconds in 2015.

Nowadays, it’s rare to work on a single task—AKA, to monotask—for an extended period. Instead, we’ve taken to multitasking—or what we presume to be multitasking.

In reality, we’re just quickly resetting our attention to jump from one task to the next. And the result? We’re wasting time and energy.

Multitasking: A human illusion

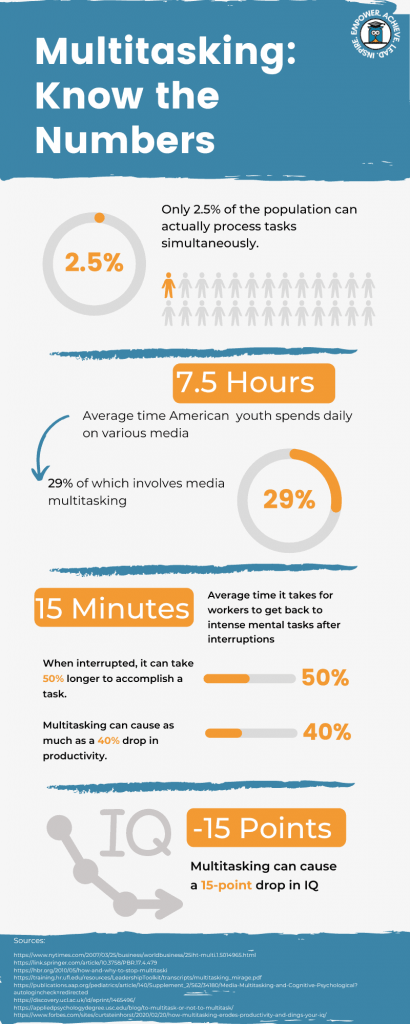

Many of us have actually fallen under a delusion—that we are able to juggle multiple tasks and thoughts at once. So it might come as a surprise when you learn that most humans actually can’t, and don’t “multitask”.

When you think you’re multitasking, research says that actually, you’re just switching between tasks. And really, the human brain evolved to monotask.

Once you recognize this, it may make more sense when you learn how much trying to juggle tasks is costing you.

If we look at the etymology of “multitasking”, it’s clear that, initially, the behavior wasn’t even associated with humans. The phrase first appeared in relation to history’s first general-purpose electronic computer. In 1966, a magazine called Datamation introduced multi-tasking in reference to the appearance of a computer’s ability to perform multiple operations simultaneously.

Since then, we’ve loosely used the term and applied it to human behavior.

Let’s get one thing straight: humans can do multiple things at once—but they won’t be as efficient or produce the work they would if they were to focus on one task at a time. For instance, you can probably successfully text or phone a friend to plan an outing while making dinner, and you can likely do your laundry while reading an email from your boss.

The thing is, you can’t fully concentrate on both tasks to the best of your ability at the same time. What happens is, you become fallible—more likely to make some type of error. Maybe you overcook the chicken, or you end up mistakenly washing your delicates.

Computers—just like humans—don’t actually do multiple things at once. They very rapidly switch back and forth. But, there’s a key difference here:

According to MIT neuroscientist Earl Miller, when computers switch among tasks, they can work more efficiently and quickly, while research on humans switching between tasks points to the opposite.

The switch-cost effect

When you think you’re fully engaged in multiple tasks, what’s really happening is that you’re switching back and forth. But your brain gives you the illusion that it’s all happening at once.

The “switch-cost effect” refers to the cost that comes with switching back and forth. The cost is that you lose time. You lose the time it takes to switch to the new task, and the time it takes to refocus back to the first task.

In 2003, the International Journal of Information Management determined that the average person checks their email once every five minutes. Even more significantly, the study found that on average, it takes 64 seconds to get back to the previous task afterward.

According to the American Psychological Association, the brief mental blocks we produce by shifting between tasks can cost us as much as 40% in productivity.

So as you can see, the costs of multitasking can add up.

What does this mean for students?

The implications here are important for understanding why students are struggling with attention span.

Multitasking, academic performance, & focus

When it comes to academic performance, multitasking is taking a toll on many students.

Multitasking and attention span seemingly go hand-in-hand. Maybe, on one hand, your short attention span leads you to try to multitask, and it becomes a cycle. On the other hand, when you multitask, you decrease your attention span.

And social media and technology are constantly drawing you in, leading you to switch your focus. As a result, your academic performance may suffer.

Research highlights that chronic media multitasking is linked to poorer cognitive abilities, because when you continually switch your focus, your brain is less able to filter out irrelevant information.

A 2019 study on the effects of academic-media multitasking (AMM) found that when students engage in AMM, they are more likely to see deterioration in short- and long-term academic performance and outcomes.

The thing is, it’s not your fault! Students may assume that their inability to focus stems from innate, individual weaknesses or lack of self-control.

Evidently, social media and technology are one of those powerful forces that have changed our lifestyles. Specifically, they contribute to our declining focus. And one study had some interesting results that reflects technology’s powerful force. Researchers were able to determine that students in online courses—compared to in-person students—were more vulnerable to distractions, since it’s easier to multitask.

Humans have a cognitive limit

Your innate human brain has a cognitive capacity. That is, if you want to do something well, you can really only do that one thing. And research shows that when you try to outperform those cognitive abilities, you just perform worse.

As noted, multitaskers generally perform worse and struggle more because they cannot filter out irrelevant information. As a result, it takes them longer to complete the task at hand.

To put our cognitive abilities into perspective, it’s helpful to think about one dangerous form of multitasking: drinking and driving.

According to the National Safety Council, texting while driving is approximately equivalent to driving while having a blood-alcohol level of .08 percent, which is the legal limit.

How to help students focus

It’s clear that technology and social media a) are not going anywhere and b) have a significant effect on the way we learn. So, it’s crucial that educators implement classroom management techniques that mitigate these effects.

Reduce class size

When you can offer more individualized attention toward students, they’ll be more inclined to actually want to learn. Plus, there’s less leeway for distraction when you’re dealing with smaller class sizes. If possible, cut down your classes.

A New York Times report on classroom size data highlights that the average primary class size is 23.1 students to every teacher, while secondary class size is 24.3 students to every teacher.

Discuss more, lecture less

Students who are already struggling with paying attention are likely going to face challenges if they’re required to sit for long periods of time, listening to lectures.

Meanwhile, when you engage in open class discussions, students will likely fare better, since they’ll be thinking about talking points and how they can contribute. In turn, as they’re engaging more, they’ll probably retain more information.

Set expectations

Unsurprisingly, when students take notes by hand versus on the computer, they have fewer avenues for distraction.

While some students have conditions that require them to use a device to take notes, the majority usually don’t. Setting a hand-written notes only policy can be helpful for students who are struggling to focus.

In addition, consider the phones. When students don’t feel pressure to stay off their phones in class, they’re more likely to check the devices every now and then. On the flip-side, if you set the expectation that students must put their phone in their bag until class is over, they’ll (eventually) have an easier time paying attention.

An increasingly connected world, disconnected focus

Due to modern technology, it has become easier to acquire and spread information. Now, this is a positive on many fronts. For instance, we can alert others of emergencies, we can more effectively collaborate when physically apart, and we can more efficiently communicate.

However, we can’t ignore the consequences. Yes, technology allows us to more quickly create and distribute information. In turn, we’ve become able to more quickly absorb content.

At the Technical University of Denmark, researchers investigated this phenomenon in regards to content consumption patterns. The researchers found that “the accelerating ups and downs of popular content are driven by increasing production and consumption of content, resulting in a more rapid exhaustion of limited attention resources.”

To sum it up, they found that, across all forms of technological communication, the volume of content we see is more rapidly increasing. We’re more rapidly taking in different bits and pieces, and spending less time on each one. And this depletes our cognitive resources quicker.

While there’s no quick fix to this multifaceted issue, necessary to improving your attention span is simply recognizing the issue. Educating yourself is a great first step—once you do, you’ll likely find it difficult to ignore the problem.

With all that being said, congratulations on making it through this article!

Author: Lydia Schapiro