Did you know that teachers, even prior to any contact, view Black girls as less innocent than their White peers?

Or that if a student of color enrolls in a high-achieving school, they’re less likely to be placed in classes that prepare them for college?

What is implicit bias?

You know that feeling you get when you find a shortcut to your destination, which means no traffic for you? Basically, that’s how we—subconsciously—feel about biases.

We love shortcuts. It’s only natural, right?

When we act on biases, we use cognitive “shortcuts” to make sense of situations. Ultimately, this helps us be as efficient as possible. Essentially, your mind’s natural tendency to seek efficiency can “trick” you into making assumptions or decisions based on a bias.

When a bias acts in your subconscious, you’re dealing with implicit bias. And there’s no avoiding implicit bias. We internalize them from history and culture, both of which have major impacts on how we view the world.

For instance, when you hear “peanut butter,” your mind probably goes to “jelly.” Two separate items, but because you constantly see them together, you implicitly group them together. Of course, something like this might have no apparent consequences.

Really, implicit biases aren’t inherently bad, but merely an evolutionary development that helps us navigate a complex world. But when we make biased decisions around other individuals, there are major repercussions.

On the extreme end of the spectrum, for instance, when people hear about someone committing a violent crime, they often visualize Black men. Because time after time, they’ve internalized the association between Black men and violence that the media and thus society perpetuate.

As research confirms, implicit bias is present in all types of environments. So it’s in your best interest to come to terms with the fact that you’re likely holding some implicit biases.

Consequences of implicit racial bias in the classroom

When teachers hold implicit racial biases, they have different lenses through which they view students.

Findings from Brookings Research highlight how, similarly to the general public, the majority of teachers tend to “hold slight pro-white/anti-Black implicit bias.”

Our biases about others can show up in various ways, such as in our preferences for who we are inclined to help/support. Research, for instance, shows that we tend to help people who are similar to us—this stems from in-group favoritism.

(In-group favoritism: our tendency to favor those within our “group”—this could be age group, race, gender, background, etc.)

Have you ever thought about who you tend to hang out with and who you’re drawn to in a crowd? Often, it seems, those people are people with similar interests, levels of intellect, and race.

And this makes sense! Being around people who are similar to you is simply more instinctively comforting than being around people who are different from you.

In the classroom, where all students are the same age and the teacher is older (and the teacher may not have much information on students’ class and upbringing), race is one of the major factors to consider when discussing implicit bias. The race of the teacher, it seems, would be a factor that could lead to in-group favoritism.

Consequently, some students will receive different treatment (namely, less or more support) than others (of course, this is often unintentional on the part of the teacher). And as a result, those students who are getting less preferential treatment might be lacking necessary support, feedback, and attention from their teacher.

Inconsistent discipline

Another way in which implicit racial bias shows up in school is in discipline.

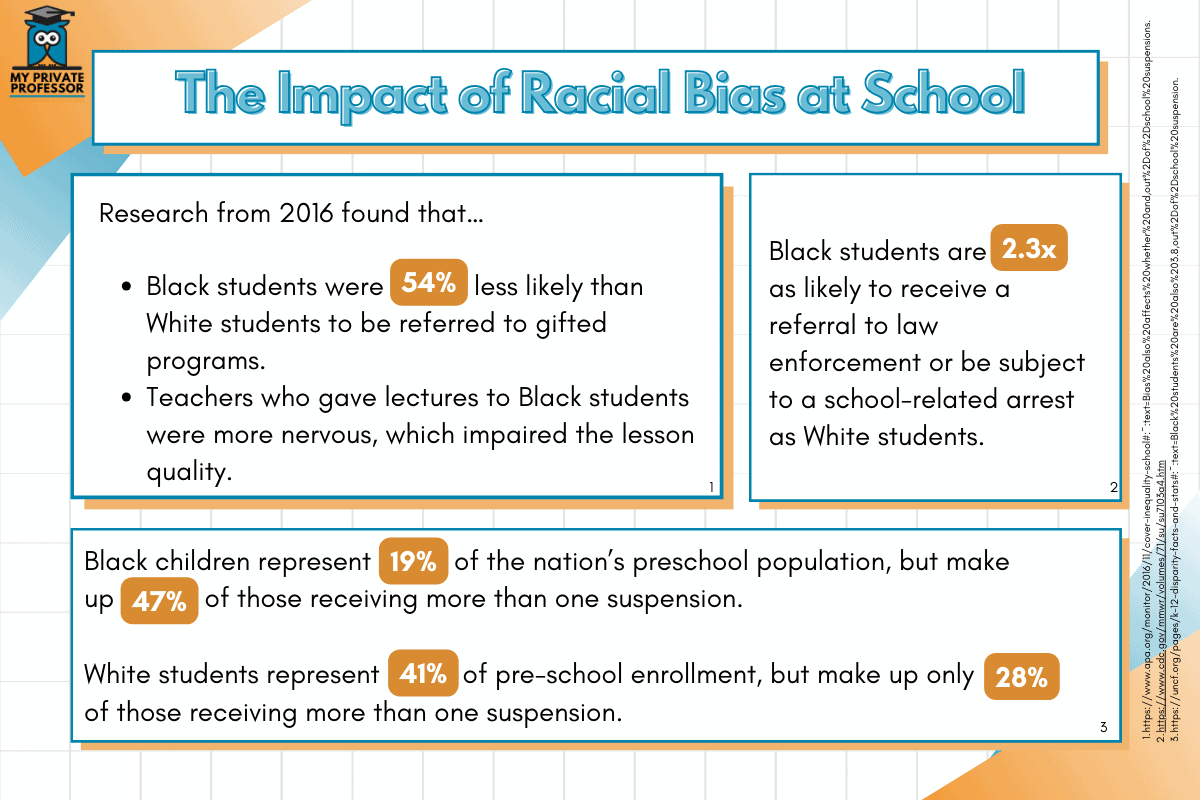

- Research shows that Black children represent 18% of preschool enrollment, but that 48% receive more than one suspension. Meanwhile, White students represent 43% of preschool enrollment, but make up only 26% of suspensions.

- A Yale University study found that preschool teachers seeking to prevent behavioral problems focused on Black male students significantly more than their peers.

- National data sets show that K-12 Black students received more frequent suspensions and expulsions than students of all other races.

Importantly, disciplinary experiences can have long-lasting effects on students. For example, experiencing just one suspension in the first year of high school doubles the chance of a student dropping out. Meanwhile, children who are expelled are three times more likely to end up in the juvenile justice system.

And once youth are in the system, they are almost seventy percent more likely to be in jail again by age twenty-five than youth not in the system (ABA).

Gifted program screening

Teachers, when they hold implicit racial biases about students, also may not be able to successfully screen students for gifted programs.

Researchers at Indiana University and Vanderbilt University found that African American children are three times as likely to be placed in gifted programs if they have a Black teacher compared to a White teacher.

Two of the researchers, Jason Grissom and Christopher Redding, looked at a well-known fact: White students, compared to Black students, are far more likely to be placed in gifted/talented programs. Of course, you could see this and assume that White students’ scores are simply better than Black students’ scores.

So Grissom and Redding looked at students with similar math and reading achievement scores in elementary school, and found that still, the White student was more than two times as likely to be receiving gifted services compared to the Black student. (This remained true when they matched up age, class, and parental health.)

So even when they have similar academic achievements, students of different races are not identified as gifted at the same rate.

The need for more Black teachers

Grissom and Redding also looked at another factor: the teacher.

They found that having a Black teacher can dramatically impact Black students’ academic outcomes by:

- Raising test scores for Black students

- Improving Black students’ behavior

- Dramatically decreasing the chances that a Black male student is suspended

Even more, a few years ago, social scientists went over records of 100,000 Black students in North Carolina and found that having just one Black teacher between third and fifth grade reduced the chance of a Black male student dropping out of high school by thirty-nine percent.

In the 2017-18 school year (the most recent year for which NCES has data), around eight in ten public school teachers in the U.S. identified as non-Hispanic White. Meanwhile, fewer than one in ten teachers identified as Black.

So evidently, the current reality among teachers—that there are far more White teachers than Black teachers—can significantly impact student outcomes and learning experiences.

Understanding a consequence of Brown v. Board of Education

As we can see, having more Black teachers can drastically impact learning outcomes for Black students.

But it’s not as simple as that.

Understanding why it’s difficult to recruit Black teachers requires recognizing that, despite resulting in the desegregation of public schools, Brown v. Board of Education had a downside.

In the case, the court talked extensively about kids, but had little to say about teachers.

In fact, an episode of Malcolm Gladwell’s Revisionist History podcast, “Miss Buchanan’s Period of Adjustment,” recognizes that the word “teachers” literally comes up once in the main text of the case.

Essentially, the case was all about the kids—the court integrated kids, but not the teachers. And yes, an incredible outcome was that the kids wouldn’t be segregated anymore. But, as Gladwell asks, how can schools take on the greatest transformation in public education and not involve teachers?

What happened after the desegregation in schools is crucial to understanding a long-lasting consequence of Brown v. Board of Education. And it happened in a place called Marlborough, Missouri.

What happened in Marlborough, Missouri?

In the early 1950s, Marlborough had lots of slave ownership and racial hostility compared to the rest of Missouri.

They had a school system that employed around 100 teachers across eight schools, one of which was an all Black school. This school was called Lincoln, and had 11 Black teachers.

One year after the Brown decision, Marlborough integrated their schools, closing Lincoln and bringing all of the Black students into the White schools. The school system then recognized that, because they were integrating all of the students into one system, they wouldn’t[t need as many teachers. So they decided to evaluate all of the teachers from the former systems.

They fired every single one of the 11 Black teachers.

After the fact, the Black teachers sued, then lost the case. Then they appealed, and lost again. In 1959, they asked the Supreme Court to consider the case.

The court refused.

After this, there was somewhat of a domino effect in the South. School systems begun to fire more and more Black teachers. According to Gladwell, within a decade, around half the Black teachers across the South had been fired.

And, Gladwell explains, the Black teachers who weren’t fired experienced major challenges and humiliations. For instance, they were forced to use the children’s bathrooms.

Today, there are far more White teachers than Black teachers. But even more importantly, there are far more Black students than there are Black teachers. While 15% of students in public schools identified as Black in the 2018-19 school year, only 7% of teachers identified as Black.

What can educators do?

The thing that is so important to recognize is that having biases doesn’t make you a bad person. Biases are simply the brain’s way of making sense out of situations. Really, it’s only human. But we can all do our part to identify and confront these biases.

Educate yourself

Just being aware of the fact that you hold biases is a meaningful step. Once you’re more cognizant of this, you’ll be better able to reflect on your behavior and be more conscious about when you may be making biased decisions or assumptions in the classroom.

Adopt a beginner’s mind

A beginner’s mind is essentially the antithesis of bias. Having a beginner’s mind means that you engage with the world without preconceptions, as if you’re seeing everything for the first time. This is difficult, as processing information that conflicts with existing beliefs can feel uncomfortable. So to adopt this mindset, you must take more effort to be aware of how you think, and basically “catch yourself” in the act.

Once you adopt a beginner’s mind, you can change the trajectory of conversations. Instead of focusing on mutual agreement, you can work towards mutual understanding, which fosters more empathy and thought-provoking discussions.

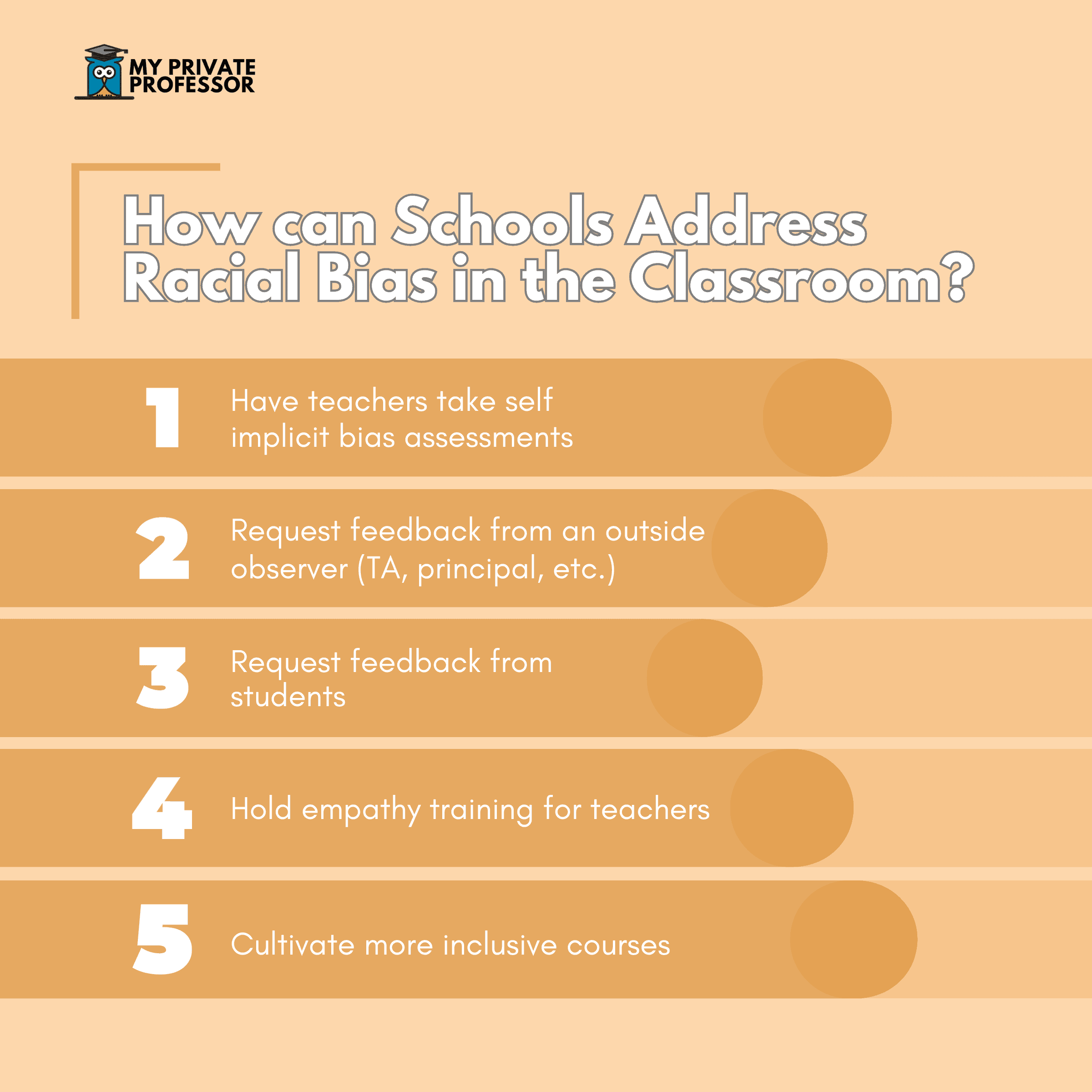

Provide developmental opportunities

For many teachers, the idea of addressing implicit biases can be overwhelming—where to start? Schools can support teachers by seeking out developmental opportunities, such as workshops focused on addressing implicit biases in the classroom.

Take an implicit bias test

Take an implicit bias test

The internet offers several free tools that gauge the extent to which you hold implicit biases, such as the Implicit Association Test (IAT). These tests can help you determine which implicit biases you hold, a great first step to becoming more aware.

Have open conversations

It’s important for students to have a voice when it comes to their experiences—specifically, around being the object of implicit bias. Teachers can better support students by dedicating time to holding conversations where students can discuss their experiences and even voice their thoughts on strategies to reduce implicit biases in the classroom.

Although these conversations may be uncomfortable, they’re necessary. Often, students who don’t experience regularly being the subject of bias may shy away from these discussions. But it’s absolutely essential that students can recognize that their levels of privilege have allowed them to do this.

3 types of biases to recognize

When considering which types of implicit racial biases may come into play in the classroom, it’s helpful to familiarize yourself with the common ones.

1. Confirmation bias

Confirmation bias is the tendency to search for information that confirms your existing beliefs, and to discount information that doesn’t. Cognitively, we do this because it’s easier to process information that aligns with our existing beliefs.

In a sense, hearing information that goes against what you originally believed is a threat. That is, a a threat to your existing knowledge, identity, and self-worth.

For instance, let’s say your zodiac sign is an Aquarius and you believe that Aquarians are particularly open-minded, creative, and eccentric. Then, whenever you meet any Aquarians who fit this description, you place more value on this “proof” that backs up your existing belief.

Additionally, you may seek out further evidence to affirm your beliefs, while ignoring information that doesn’t align with your belief.

If you implicitly associate crime with Black men, you may seek out statistics and events that confirm this association—but meanwhile, you’re forgetting about all the other information that counters that association.

In terms of minor topics like zodiac signs, confirmation bias can be harmless. But when it comes to racial bias, it can be detrimental.

2. Hindsight bias

If you went to a private school for pre-K, you might know that there’s some unfairness when it comes to admissions. Although there’s usually an admissions “test” (which might involve talking, working with colors, blocks, etc.), it doesn’t usually actually measure intelligence. Meanwhile, there are other factors involved.

For example, if you had older siblings who attended the same school, you have a better chance of getting in.

Imagine you’re reflecting on this experience with friends. Your friends didn’t get into the same elite private pre-K that you did, and instead of mentioning that you had multiple siblings that were in the school and that your parents knew the admissions people, you attribute your luck to skill. Skill on the pre-K admissions test.

This is a type of hindsight bias—when you look back and attribute luck to skill. Essentially, this reflects how it’s difficult to remember the uncertainty/unawareness you once had.

It’s important here to recognize that you can’t perfectly recall past ignorances. (In this case, the lack of action on your part when it came to getting into pre-K.) Identifying this human flaw can help us develop more compassion and appreciation for the journeys that others are on and the struggles they may face.

3. Overconfidence bias

Often, we have overinflated perceptions of our own abilities. As a result, we may act and feel competent in areas in which we are generally unqualified to speak on. This is the overconfidence bias, which arises when we approach conversations arrogantly, believing we have the answers.

Think back to a time when you were enrolled in a class that seemed like a piece of cake.

Naturally, before the big test, you felt confident. You didn’t review all the past material, and generally, didn’t do much to prepare. But once seated at the exam, you realized that there was a lot you didn’t know.

You trusted your knowledge and skills, so you refused to open your ears to information from others (namely, your teacher). This is the result of the overconfidence bias.

In a class discussion about implicit bias, one of the goals should be to learn. When you’re overconfident, your ego serves as a barrier to this outcome. Being honest (with yourself and others) about your current beliefs is thus of the utmost importance.

Final thoughts

At the end of the day, holding onto implicit biases can really limit anyone’s ability to live life to the fullest. Why? Because these biases can hinder conversations, relationships, and in general, interactions. And as a result, they obstruct creativity, innovation, and positive change.

In the classroom, cultivating awareness around how the human brain works—and subsequently addressing implicit racial bias—is critical for fostering a tolerant, empathetic, and conscious classroom. And with any small steps come greater changes.

So, each time you make steps to elevate the classroom in this sense, you’re setting the stage for larger-scale changes.