For a long time, I was trying to think of an article topic based on my personal experience in school. I was searching my mind. I was trying too hard, I think. I kept trying to pull—or force—something out.

Here’s what was happening: rather than thinking about my true experiences through my K-12 years, I was trying to come up with something that, I thought, would make for a meaningful story.

Essentially, I was looking to craft that classic intro-rise-peak conflict-fall-resolution story.

In a few words, I was searching for some struggle, conflict, or challenge—which I identified during those years, then overcame.

But it came to me the other day—that I was searching for something that I may not have experienced. And I was searching for the wrong reason—to write the story that I thought readers wanted to hear.

Acknowledging your own privilege

I realized, if I’m actually honest with myself, when reflecting on my K-12 years, what come to mind isn’t strife. It’s privilege. Not directly, but, looking back on those years, I mostly remember fun, positive, happy, and/or memorable experiences. And to some extent, I was able to experience those opportunities due to my privilege.

Let’s look at some examples:

- I could get a tutor if necessary

- I could get a top-notch graphing calculator

- I could nurture my mental health by participating in extracurriculars

- soccer, basketball and tee-ball leagues; drum, guitar, and piano lessons; dance and ice-skating classes; tennis lessons; art classes

- I hosted birthday parties during which I could socialize with my friends

- I was able to play on school sports teams

- I could go on every field trip

- I had functioning lights, heat, air conditioning, and a bed, which allowed me to get quality sleep

- I never had to worry about going hungry

- I had all the necessary school supplies

- I didn’t feel self-conscious about my physical appearance in the classroom

Writing this, I will admit, feels a little awkward and unnatural. It’s kind of like doing the privilege walk activity on paper.

But the thing is, that’s part of the problem. It feels uncomfortable to talk about our own privilege. But the truth is, it’s the truth! The amount of privilege you held as you grew up is just a piece of your identity. And here’s another truth: the level of privilege you grew up with doesn’t cancel out the hardships you faced.

Here’s the thing—everyone faces their own unique struggles. But identifying outcomes or struggles due to lack of privilege is a different ballgame.

All students struggle – regardless of privilege

There are many reasons why students struggle in school. Evidently, experiencing conflict during these years is inevitable. You’re not going to sail through without any challenges.

Maybe you didn’t get the role you wanted in the musical. Or perhaps you constantly had issues with a teacher.

But then there’s hardship that arises due to a lack of privilege. And this is attributed to genetic makeup. Luck of the draw.

Some ways in which lack of privilege may limit students in school:

- Not affording going on all the field trips

- Not affording hot lunch every day

- Not going to birthday parties that involve costs (transportation, presents, equipment, tickets, etc.)

- Not being able to come to school every day feeling well-rested

- Not being able to purchase all the school supplies you need

- Getting insufficient nutrients (which affects concentration, mood, and productivity at school)

- Not being able to host birthday parties of your own

- Not attending school-related events or after-school programs

- Not purchasing various trendy items (think: silly bands, Webkinz, sticker books) that your peers have

- Not participating on school sport teams

- Not receiving tutoring

As you can see, a student’s experience in school can vary greatly depending on how much privilege they hold.

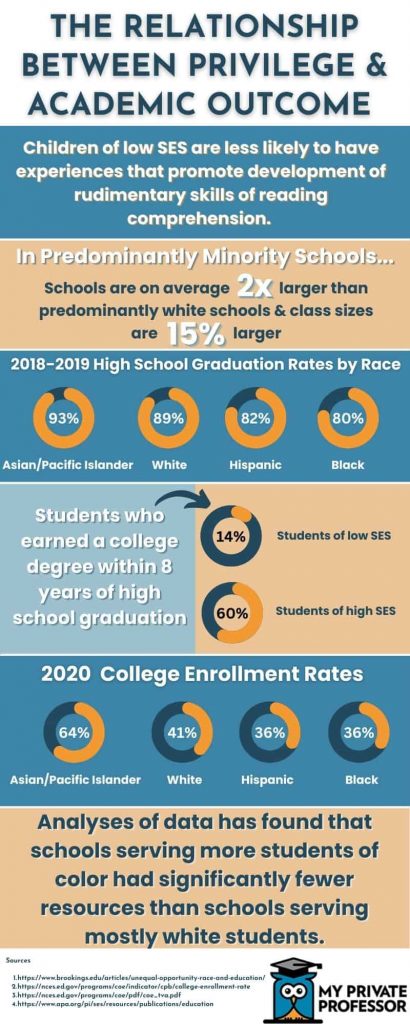

Patterns of privilege-related outcomes in research

An important part of understanding and discussing privilege is seeing the clear picture—in numbers. What I mean is, it’s helpful to look at empirical data and patterns around the relationship between privilege and academic achievements/outcomes.

Below are some noteworthy data points that shed light on this:

- A study analyzing how privilege affects academic performance found that students scored higher in all subjects when they had more resources in their country, family, or school. (1)

- Low SES in childhood is related to poor cognitive development, language, memory, and socioemotional processing. (2)

- In a study on students in urban and suburban schools, Black students had significantly lower reading and math scores than White students. (3)

- Over the past decade, average math and reading test scores in California have risen for all student groups except Black students. Test score gaps among most student groups either remained steady or narrowed—other than the gap between Black and white students, which increased. (4)

- In 2009, students in the bottom 20% of family incomes were 5x more likely to drop out of high school than students in the top 20% of family incomes. (6)

Collective discomfort around talking about privilege

Today, it seems that so many of us are uncomfortable talking about privilege. Especially, our own. And I get it—there’s the time and place.

On one hand, it’s obviously not always an appropriate subject to raise. But on the other hand, considering how much it seeps into our lives, it’s definitely a necessary subject to discuss.

When I was in high school, we had several days of the year allocated for special workshops or guest speakers. For the most part, we discussed equality, intersectionality, and privilege. As a heterosexual, caucasian female student, I held my unique perspective. But I can say with confidence that there was one thing that most of us collectively observed:

Whenever privilege was the sole focus, those with—seemingly—the most privilege, seemed most averse to discussing the issues at hand. But it was more than averse—it was sheer discomfort.

I certainly felt it, but I didn’t stop to really question where all of the discomfort came from. Now I will.

Why are we hesitant to talk about our own privilege?

And if the main reason is discomfort, why are we so uncomfortable?

1. Denial

When we look at our accomplishments, we like to think that they are products of our skills, knowledge, talent, and innate traits. We don’t want to think that something, which may be randomly assigned (like race or sexuality), had anything to do with our achievement.

Oftentimes when discussing privilege, we note how it may have contributed to where we are now, and the opportunities that have been made available to us.

It can be very difficult to come to terms with the fact that part of your identity—that you don’t control—helped you get to where you are now. And one instinctive way to cope with this discomfort is denial.

2. Guilt

Once you have the privilege (ha!) of understanding how pieces of identity can help or limit someone, you may feel unsettled.

It’s understandable, after comprehending the nature of privilege, that you may feel this way. For instance, upon learning that your race, which you didn’t choose, helped you get into college, you might feel guilty. After all, how is it fair that traits are randomly assigned, and then influence our outcomes in such significant ways?

You may actively recognize that those who are less privileged than you may look at you and see undeserved luxury—which can often translate to them holding resentment or anger.

Maybe you assume that they look at you and do just that: resent you. Hence, guilt.

Yet this isn’t your doing or fault.

As a reminder, here’s what privilege is:

Benefits or advantages you inherently receive due to your identity.

So through understanding the true nature of privilege, you can recognize that you don’t need to feel guilty. And that really, feeling guilty can just bring you right back to being so uncomfortable around discussing privilege—which contributes to the problem.

That is, when you hold onto that denial and guilt, it’s much more difficult to comfortably engaging in meaningful conversations about privilege.

And in reality, holding onto so much guilt impacts those around you just as much as it affects you. When you are so resistant to discussing privilege, you prevent others from taking strides around such a complex topic.

3. Desire for empathy

We all want others to recognize our hardships. That’s a fact. That’s why it’s not unusual, in a conversation about privilege, for people to get defensive. The important thing to remember is: everyone faces conflict. Everyone struggles at points in their lives.

But even if you are going through something that seems like it’s more difficult than anything anyone could be going through, you can’t pit general hardships against systematic disparities.

So really, when you think about privilege in terms of its definition (based on your inherent identity), it’s a bit easier to recognize that there’s no use in trying to resist acknowledging your own privileges for the sake of allowing people too see that you, too, face challenges.

The Headwinds/Tailwinds Asymmetry

There’s another factor to consider when you think about why you may be so resistant to identifying your own privilege. It’s a cognitive bias called the headwinds/tailwinds Asymmetry.

A cognitive bias is essentially an error in thinking; it’s a shortcut you use that makes the processing a little simpler.

The headwinds/tailwinds asymmetry refers to the way in which, as humans, when reflecting on our experiences, we tend to weigh our obstacles, challenges, and/or disadvantages more heavily than the positives.

So how does this relate to privilege?

Very directly, actually.

This cognitive bias comes into play when we get defensive. When you’re engaging in a conversation about privilege, you might go on the attack, thinking: Why are all the obstacles I’ve faced being discounted right now?

This may result in you trying to exemplify how you’ve struggled and why your challenges have been so significant.

We do this because we’re motivated to view ourselves in a positive light (i.e. having the perception that we’ve overcome a ton)—and placing more weight on obstacles than on achievements or advantages, allows us to do so.

Final thoughts

All that being said, you may be thinking, what now?

Well, the fact that you took the time to perhaps identify your own privilege is a big step in itself. Plus, you’re now equipped with new knowledge—that is, fundamental reasons why you may avoid talking about privilege.

Remembering and accepting the facts is important:

- Everyone has different levels of privilege.

- The amount of privilege you have can and will affect a student’s school experience.

- You can’t take privilege out of the equation when it comes to academic achievement.

Taking the step to even reflect on your life and think about your own privilege is a great step toward raising awareness around issues surrounding privilege. Once you acknowledge that privilege has affected your life in x and y ways, you’re also opening yourself up towards being more tolerant of other people’s experiences and perspectives.

Below are some tips for encouraging open conversations around privilege:

- Educate yourself about privilege and identity—utilize books, articles, podcasts, videos, and any other resources at your disposal.

- If you see something that seems like unfair treatment based on someone’s identity, say something.

- Reframe conversations around privilege: start by acknowledging that everyone faces hardship, and that identifying privilege doesn’t cancel that out.

For educators:

- Develop classroom ground rules and expectations

- Define terminology around topics related to privilege

- Don’t force anyone to speak on their experiences

- Connect discussions to both current and historical events

References

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/250184830_Effects_of_Resources_Inequality_and_Privilege_Bias_on_Achievement_Country_School_and_Student_Level_Analyses

- https://www.apa.org/pi/ses/resources/publications/education

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7797342/

- https://edsource.org/2021/new-data-shines-light-on-student-achievement-progress-and-gaps-in-california-and-u-s/648321

- https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/pdf/coe_tva.pdf

- https://www.apa.org/pi/ses/resources/indicator/2013/05/poverty-dropouts

Author: Lydia Schapiro