Think about any particular class you’ve ever taken in school. Like most classes, it probably involved a good amount of speaking—sharing opinions, asking questions, and raising concerns.

In your classes, would everyone speak the same amount? Or was there more variety? I’m guessing the latter.

Here’s what it usually looks like:

Similarly, during group presentations, you don’t usually see each student speaking to the same extent. And even during lunch and after-school programs, it’s clear that some students are speaking more than others.

Teachers and students alike can observe this. But the problem is, they often don’t grasp what’s really happening. They see some students speaking less than others—and then attribute that to shyness.

But usually that’s not the case.

The level at which students choose to speak is likely directly related to where they land on the introversion-extroversion scale. But sadly, in the classroom, teachers (and students) often make incorrect assumptions about the quieter students—assumptions such as:

- They didn’t do their homework

- They don’t understand the material

- They’re unwilling to speak

- They’re chronically shy

And the consequences here may be dire.

There is a fundamental misunderstanding of introversion vs. extroversion

Before diving in, I’d like to note that I believe that collaboration, group work, and socialization are all major and necessary components to quality education.

But, introverts make up an estimated 25-50% of the population—simply put, it seems pretty illogical to cater the majority of the learning process to extroverted students.

Introversion and extroversion are personality traits

Consider this: You don’t see teachers expecting passionate and assertive students to change their personality.

But as it seems, teachers expect introverted students to fit their behavior to match that of their extroverted peers. It’s very common for teachers to heavily grade students on class participation. Sometimes, in group presentations, teachers grade students solely based on verbal performance.

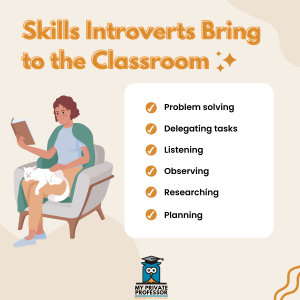

Meanwhile, it’s uncommon for teachers to assess students’ ability to listen, reflect, strategize, and observe (common introverted-related skills). And introverted students tend to take on more quiet, solitary tasks which, despite being critical to a group’s presentation, are not graded heavily.

This puts these students at a disadvantage. Because they are more likely to do the more individualized tasks, they may not get as much credit as their extroverted peers.

Teachers often coax introverted students to speak up—assuming that these students are shy. But this is a flaw in the system.

Introversion vs. extroversion is simply a personality dimension—just like being impulsive vs. methodical.

Introversion is not a synonym for shy

Here’s what a lot of people don’t realize: introversion is not the same as shyness.

While both introverts and shy people are often the quieter ones in a room, the reasons why a shy person and an introvert avoid speaking are usually completely different.

Introversion is related to how someone responds to stimulation. Typically, introverts lose energy when in highly stimulated-environments, and gain energy in less stimulated environments (and the opposite is true for extroverts).

Meanwhile, shyness is related to social anxiety—specifically, a fear of negative judgment or rejection.

We need to recognize the value in introverts, rather than trying to turn them into extroverts

The irony here is that, it seems that schools wouldn’t function if all students behaved like extroverts. Like the yin and yang forces, extroverted students need introverted students. Introverts are often the ones listening, contemplating, and observing, which are critical skills for identifying errors, gathering information, and devising a plan.

Meanwhile, extroverted students tend to take less time to grapple with ideas—and in turn, often fail to provide themselves with the chance to think critically. And as we know, critical thinking is one of the most important skills that students need to succeed.

By continually misunderstanding introverted students, we’re failing to take advantage of and honor the valuable skills that they hold.

We misinterpret these students for being shy, scared, or confused. But in reality, we’re not providing introverts with the space that they need in order to thrive.

Most of us are extroverts and introverts

According to Positive Psychology, most of us are neither purely introverts or extroverts. Just like most personality traits, there’s a scale on which we measure ourselves. And with extroversion vs. introversion, it seems that most of us lie somewhere in the middle.

Perhaps you thrive off your friends’ energy—but only for a couple hours, after which you need quiet time. That’s normal. Most of us fall somewhere in between the two extremes.

So then, what’s with the divide? Wouldn’t it benefit everyone to recognize that most of us have both tendencies—and then, to develop institutions and systems that honor both?

I would say yes.

But first, let’s take a step back and look at how we even got here.

The Extrovert Ideal

Author Susan Cain coined the term, the “Extrovert Ideal”, which refers to how many Western cultures have developed a rigid idea of the ideal individual.

The Extrovert Ideal simply points to that collective belief that the ideal individual is someone who holds extrovert characteristics—they’re outgoing, thrive in the spotlight, are confident and assertive, and love to take risks.

How did The Extrovert Ideal originate?

In the mid-20th century, the American population was shifting from residing in rural areas to more suburban/urban spaces. There, people were confronted with change. In small towns, inhabitants generally knew most people with whom they engaged—meanwhile in cities, they stumbled upon a lot of unfamiliar faces.

Consequently, salespeople began to sell themselves to customers through presentation and personality. During that time, employees found themselves in an interesting position: in order to stand out and succeed, they had to emit certain traits in an interview—think: bubbly, charming, magnetic.

Plus, this was occurring at the same time as the rise of movie stars. And as you can imagine, dealing with fans and paparazzi, movie stars were under pressure to tap into those extroverted traits—which became the standards for the ideal character.

In her book, Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can’t Stop Talking, Susan Cain

describes this period as America’s transition from a Culture of Character to a Culture of Personality.

Cain highlights how there was a shift in content and propaganda from inner morals to outer appeal. That is, one of the previously major pillars of human morale, virtue, morphed into something else: personality.

And Cain points out that we can observe this by looking at self-help and advice books. These guides moved away from using words like ‘duty,’, ‘integrity,’ and ‘work,’ to words like ‘magnetic,’ ‘dominant,’ and ‘forceful.’

I am in no way suggesting that we should simply mold schools to fit introverts’ needs. Instead, it seems reasonable enough that schools should cater to the needs of all students.

After all, introverts seemingly make up ~one-third to half of the population. Does that surprise you? Let’s look at why.

The friendship paradox

The friendship paradox suggests that, on average, your friends are more popular than you. This seems confusing, because, of course, this can’t be true for everyone—you may be thinking, I know plenty of people who are less popular than I am and, someone always has to be more popular!

But the key word here is average.

This paradox reflects our misconception of how many extroverts are in the world. That is, we seemingly observe that most people around us are extroverted—then, we assume that extroverts make up the large majority.

But here’s the flaw: on any occasion, statistically speaking, you’re more likely to speak, spend time, or become friends with an extrovert than an introvert. And this is simply due to the contrasting ways in which introverts and extroverts replenish their energy.

On one hand, extroverts get energy from being in highly-stimulating environments; on the other hand, the opposite is true for introverts. So generally, you’re more likely to be engaging with an extrovert.

So of course, on average, your friends will be more popular than you—and for the sake of this explanation, I’m using “popular” to describe how many friends one has.

Essentially, it seems as though there are significantly more extroverts than introverts. But this is only because your sample is usually not representative of all individuals. Rather, it’s biased toward extroverted people.

Sample size matters

Think about it like this:

Imagine you attend a painting group that meets weekly—but you’re only trying it out one time. As you look around, you realize that most people seem to be more creative than you.

But this makes sense, right? If you occasionally pick up a brush, then this is what you should see. The people in the class attend weekly, so they’re probably the ones spending lots of time on their art. Thus, the sample is not representative of all individuals—it’s biased toward artists.

Ultimately, we have a collectively skewed perception of the prevalence of extroverts—and this only reinforces notions surrounding The Extrovert Ideal.

What are the implications of The Extrovert Ideal for students?

As a result of The Extrovert Ideal, many of our institutions and communities reward extroverted behaviors and criticize introverted behaviors. Rather than viewing introversion and extroversion as two contrasting personality types, The Extrovert Ideal has led us to see extroverts as superior.

In school, the combination of misunderstanding introversion and the ingrained extrovert ideal results in teachers trying to fix students instead of accepting them, and then actually learning from their strengths.

For the introverted student, this ideal can lead to challenges in the classroom. In a setting where they feel obligated to speak up as much as possible, introverted students don’t feel as comfortable as they would in a space that provides them time to prepare what they’ll say. Consequently, this places introverted students at a disadvantage.

And what happens when students are consistently in an environment that drains their battery? They experience school-related burnout.

On top of that, everyone else is at a disadvantage too, because they’re missing out on all the great ideas introverted students might have (but don’t share).

Let’s cater to both introverts and extroverts

During the pandemic, many students faced challenges shifting to remote school. But it seems, many introverted students preferred online learning.

Unfortunately, though, the transition back to in-person school left these students disappointed to realize that they no longer could enjoy their solitary space. Their precious solitary space which allowed them to stay focused for longer and come to class with more energy.

Group work is certainly beneficial for all students—it encourages communication, collaboration, and open-mindedness. At the same time, though, it’s crucial that students gain skills such as critical and independent thinking.

“When you’re working in a group, it’s hard to know what you truly think. We’re such social animals that we instinctively mimic others’ opinions,” explains Susan Cain.

It’s crucial for students to learn how to form an opinion on their own—and then come back to the group and share. In addition, listening and observational skills can enable students to build tolerance to exploring various perspectives.

And, it’s important that there’s more of a balance between extrovert-friendly and introvert-friendly work.

It seems that catering some of the learning experience to introverted characteristics works to everyone’s advantage. Because then, educators are molding all students—and by doing so, creating opportunities for everyone to learn better from each other.

Neglecting to cater to introverted students doesn’t serve anyone. In fact, it hurts everyone.

Shouldn’t we mold our institutions to fit the people, instead of doing the opposite?