As humans, we strive to differentiate ourselves from others. But seemingly, there is this one thing we have in common. No matter how many unique oddities we adorn ourselves with, we all want to get up in the morning and do good. We seem to have this innate desire to put our motivation toward creating something positive.

Psychology offers theories to explain human motivation, but some of the early ones don’t really explain it all.

For instance, instinct theory (1870s) suggests that motivation is biological. It posits that we behave in certain ways for the sake of survival. For example, if you see a bear heading your way, your fight-or-flight instinct will come into play, pushing you to move away from the bear in an effort to survive.

Or, take drive theory (1943), which suggests that our physiological needs push us to reduce these needs in order to maintain homeostasis (which is the state of balance in your body’s physical systems necessary for function and survival).

For example, if you’re yawning at your desk and can’t keep your eyes open, your need is sleep, and your drive is sleepiness. So your drive-reduction behavior is sleeping. There’s a need, a result of that need, and an ensuing action to reduce the need.

Similarly, Maslow’s hierarchy of needs (1943) says that our desire to fulfill our fundamental, physiological needs drives our behavior.

Motivation isn’t black and white

Today, most of us fortunately don’t live in constant fear of being eaten by predators. Meanwhile, I’m sure you can think of many things you do that aren’t motivated by either homeostasis or survival. Evidently, then, the question is, what else drives our behavior?

Have you ever done a jigsaw puzzle? Or hula hooped? Or replaced a roll of paper towels? What do all of these tasks have in common? Likely, none of them were motivated by your physiological or survival needs.

So as you see, while the theories above may explain some of our actions, they can’t paint the full picture of motivation. Because in reality, we’re complex beings. And so we can’t attribute every one of our actions to a method of survival or preserving homeostasis.

Consider the following example:

There’s a link between depression and overeating. In this scenario, you may not feel “hungry,” per se, but nevertheless, you eat. And the reason is that foods high in fat, sugar, and carbs momentarily combat the negative feelings associated with depression. Clearly, in this case, you’re not motivated by your body’s physiological needs or the need to survive.

Rather, you’re driven by your emotional state, which is just one of the various factors that can affect motivation.

Lacking motivation is a common student predicament

As much as our world is increasingly becoming more digitized, we’re not — and hopefully won’t ever be — robots. As much as we may yearn for it, we can’t turn motivation on and off with the switch of a button.

Thinking back to my time as a student, it seems as though when my friends weren’t getting good grades, the problem often wasn’t an issue of intellect or skill, but of motivation.Today, thinking about how often I hear someone identify a resolution or goal and never follow through, it seems that everyone, at some point or another, has difficulty finding motivation.

To see how true this was, I did some research.

Indeed, I found that lacking motivation is a pretty ubiquitous challenge. A 2022 survey asked students what their biggest challenge had been in the last year, and one of the most common answers (64%) was ‘keeping motivated in my studies and/or job search.’

In addition, a survey found that among undergraduates during the online learning period, on average, the biggest obstacle for students was lacking motivation.

In school, students may know that they have a big test coming up. Their inner voice may be saying that it’s time to study. But in certain cases, students neglect this voice and don’t study. Evidently, motivation doesn’t always work as we’d like it to.

But as we know, motivation is a key player in academic success. It can majorly impact academic achievement and outcomes, both in the classroom and beyond. So it’s critical to understand more about the mechanisms of motivation in order to understand how best to nurture students’ motivation.

Your brain on motivation

When you experience motivation, your brain releases dopamine, which travels to the nucleus accumbens (responsible for mediating reward behavior). Your brain then provides helpful feedback about whether something good or bad is about to happen. Consequently, you respond to either minimize the predicted threat or maximize the predicted reward.

In a Vanderbilt University study, scientists found that those who were inclined to work hard to gain rewards had higher dopamine levels. And dopamine was found in the striatum and prefrontal cortex, two areas linked to motivation and reward.

Meanwhile, for those who were less willing to work hard for rewards, dopamine was only found in the anterior insula, the region associated with emotion and risk perception.

This tells us that dopamine responses vary from student to student. So evidently, some students inevitably must thus work harder than others to unlock their motivation. Consequently, it’s vital to understand how to help students do this.

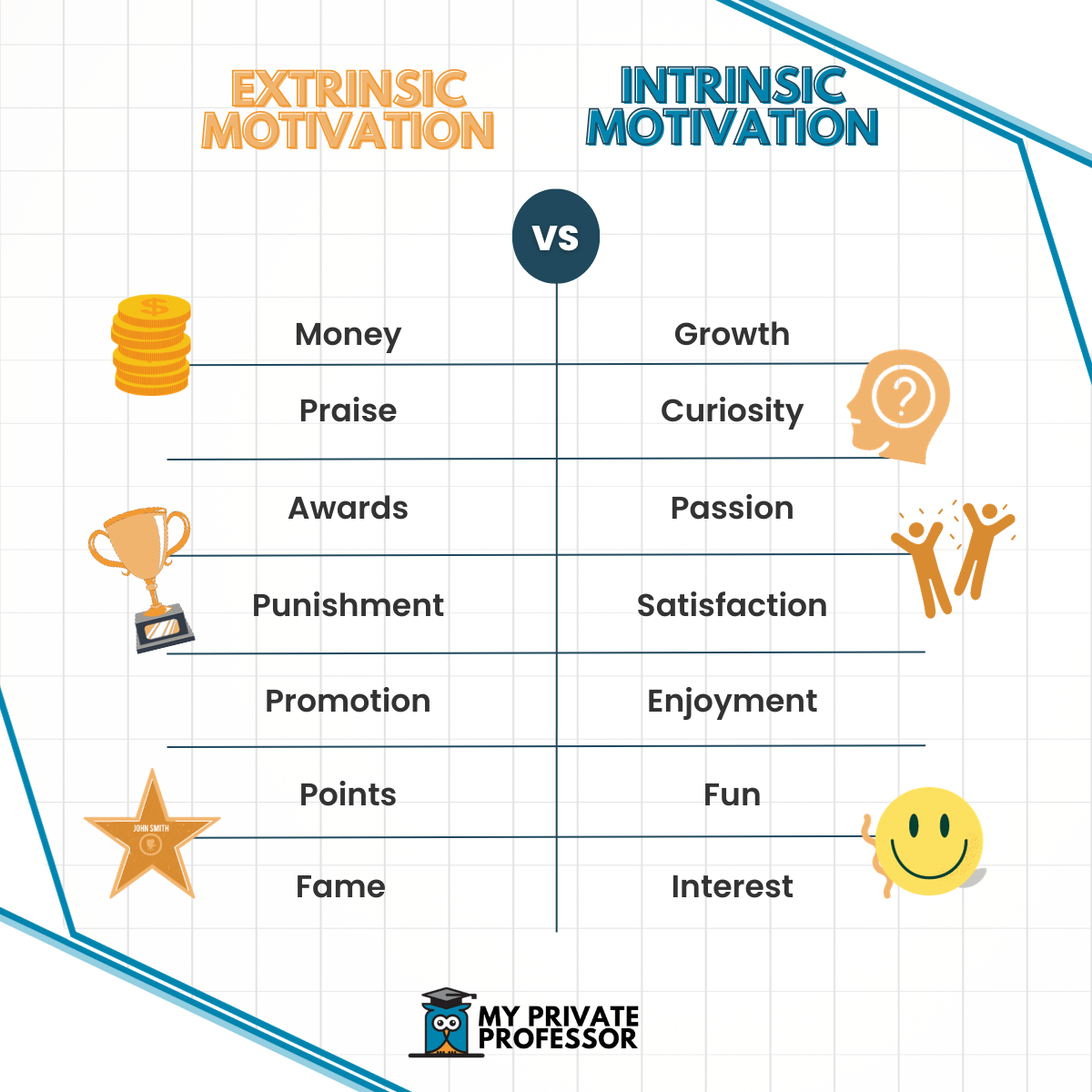

Intrinsic vs. extrinsic motivation

When thinking of motivation in the classroom, there are two main types to consider. Think about the following scenarios:

1. You’re a student in American History, which you don’t find particularly interesting. Yet, you’re committed to doing well in the class. Why? Because you know it’ll look good on your transcript, and that getting a good grade will improve your chances of getting into Stanford.

2. You’re enrolled in the same course, and you find it fascinating. You love getting into the nitty gritty of colonization. And you find it captivating to discuss the constitution’s origins. So you study into the late hours of the night until you can’t keep your eyes open. Why? Because you love it.

The former scenario depicts extrinsic motivation, whereas the latter scenario portrays intrinsic motivation.

In both cases, you’re studying hard. But the difference is what’s driving you. In the first instance, you’re motivated by the tangible reward (the grade). In the second scenario, your motivation stems from your innate interest in the subject.

With extrinsic motivation, you’re motivated by an external factor (i.e., getting a good grade, avoiding a penalty, money). And with intrinsic motivation, the reward is the activity itself.

Which is more important for students?

The million dollar question.

Well, both intrinsic and extrinsic motivation are important for students, but in different ways, and at different times.

Extrinsic motivation, research shows, can yield short-term results. But, in the long-term, using extrinsic motivation as a main driver can be detrimental. Why? As psychologists suggest, constantly using external rewards can create dependencies.

In one study, researchers conducted two experiments to look at how grades motivate students’ motivation and interest in learning. The researchers looked at three conditions:

- A harsher-grade condition (generally resulted in lower grades)

- A high-grade condition (generally resulted in higher grades)

- A no-grade condition

The researchers found that high grades provided a boost in interest and motivation, yet only for a short period. Interestingly, they found that students in the no-grade condition (no external rewards) had more motivation and interest than students in the standard-grade condition — both short- and long-term.

Intrinsic motivators for long-term success motivation

While having a grade as a reward increased interest in learning, it didn’t predict long-term motivation. Meanwhile, not having any extrinsic motivators increased motivation for similar tasks. In the no-grade condition, students only had their intrinsic motivation to rely on. And this resulted in more long-term motivation.

In another study, researchers looked at people who loved to do puzzles simply due to the satisfaction of completing them. The researchers found that after they offered financial rewards, participants had less motivation to complete the puzzles.

Evidently, when you add external motivators into the mix after someone is already motivated, that initial drive may decline.

With intrinsic motivators, students put forth more effort, pursue more challenging tasks, and gain a more profound understanding of the information they study. Generally, research shows that intrinsic motivation leads to better learning outcomes.

When do students feel motivated?

Self-determination theory addresses the fundamental drive behind students’ motivation. According to the theory, there are three underlying factors that must be present in order to fully unlock student motivation: autonomy, competence, and relatedness.

This means that students must feel some level of agency over their work, they must feel as though they are capable, and they must feel some level of connectedness to the work at hand.

What can teachers do?

Encourage autonomy by giving students agency.

Having some agency in the classroom empowers students to feel more involved with the work they’re doing. And as a result, they’ll invest more of themselves.

Teachers can promote agency by providing options when it comes to tasks and assignments (i.e., Create a presentation using PowerPoint, a physical poster, a story, or a video).

Teachers can also request student feedback about what they want to learn about and their preferred methods of learning, showing students that they do have a say.

Elevate feelings of competence by focusing on individual progress.

People are constantly discussing the importance of “energy.” Seemingly, energy is just what one brings to an environment (an aura, essence, or “vibe”). And, energy can easily seep from one person onto another.

For example, when a student feels that their teacher is doubtful of their ability, the student may internalize this and as a result, become less confident. This can be detrimental to motivation — and as a result, their performance in school.

Research shows that, in fact, low teacher expectations negatively impact student achievement. So, it’s critical to foster an environment that uplifts students and promotes competence.

We’ve all experienced being the victim of an unfair comparison. Maybe your older brother was a consistent A-student and your parents would subtly compare your “acceptable” B+ to his stellar scores. Or maybe, when you were subbing for the future pro-athlete goalie on your soccer team, your coach questioned why there were fewer saves during the game than usual.

Research shows that comparing yourself to others can prompt negative emotions and decrease self-esteem and psychological well-being.

The thing is, we actually seek these comparisons out, usually unknowingly.

According to cognitive dissonance theory, we fundamentally strive to achieve consistency between our thoughts and behaviors. And we look to others to affirm our consistencies. So if a student believes that he should be proficient in algebra and got an A- on the final exam, but sees that his peer got an A, he may feel a gap between where he is and where he feels he should be. As a result, he may measure himself against his friend.

Teachers can cultivate a better classroom environment by simply acknowledging each student’s individual progress without comparing it to other students’.

Promote relatedness by incorporating students’ interests in the lesson.

Unsurprisingly, it’s often more enticing and easier to learn about something that we can relate to than something to which we feel zero connection. In school, teachers can help students better engage with material by relating lessons to students’ interests and current events.

For instance, an English teacher of students in New York City might open up a class discussion about a scene in Lord of the Flies by asking, “If you were stranded in Brooklyn with a group, and your leader announced that he’s fleeing, what do you do?”

What else affects students’ motivation?

That being said, there are other factors (outside of the classroom) that affect students’ motivation. Three major ones are physiological state, environment, and past experiences, according to research.

It’s critical for teachers to address and help students diminish any de-motivators (factors that decrease motivation).

For instance, if a student has historically done poorly in math, they may very well be apprehensive about their mathematical skills. Teachers can address this by teaching students about growth mindset and encouraging them to shift their perspective. For instance, teachers can encourage students to add “yet” to their vocabulary. (“I haven’t mastered trigonometric functions…yet.”)

In addition there are other common individual factors that can be de-motivators. Think: sleep deprivation, sickness, stress, and trauma. All of these factors can take up all of students’ energy — consequently, they’ll have less of it to use to tap into motivation.

Unlocking short-term motivators

Although some parts of cognitive function are completely out of your control, there are certain things you can do to automatically activate students’ motivation. That is, there are a few “states” that can unlock motivation. These are: curiosity, anticipation, and relevance.

When in these states, your brain activates motivation by releasing certain neurochemicals — dopamine, norepinephrine, and cortisol.

And there really are all sorts of ways for teachers to induce these states. For example, a middle school science teacher may spearhead a discussion on plant biology by asking students, “what is the only fruit that carries its seed on the outside?” And instead of telling them the answer, the teacher can allow the students’ curiosity to brew, and wait until the end of class.

Teachers can incorporate stories into almost all types of lessons — and through these stories, teachers can use cliffhangers to induce anticipation.

As for relevance, it’s important for teachers to recognize what’s happening in the world outside of the classroom (within students’ interests). Then, teachers can make comparisons and relate the coursework to something with which students feel an actual connection.

Addressing common student “de-motivators”

Here’s what teachers can do to nurture these areas and in turn boost motivation amongst students.

Hold regular check-ins.

To make sure students are doing well, it’s important to regularly check in with students. Teachers can hold casual meetings that students set up at their leisure. Or, this can be more formal, where students have scheduled check-ins, perhaps bi-weekly.

Create a suitable environment.

Have you ever heard that a cluttered space makes for a cluttered mind? Well, it’s actually true — research shows that working in a cluttered environment can cause increased stress and anxiety. As such, the classroom environment can either help or hurt students’ learning.

Here are some things teachers can do to improve their learning environment:

- Regularly clean and organize the classroom.

- Minimize distractions.

- (Note-passing, cell-phone use, interrupting, shouting, etc.)

- Keep the classroom at a suitable temperature.

- (68 – 75ºF during cold months, 73 – 79ºF during warm months)

- Bring uplifting items into the classroom (posters, lights, flowers, etc.).

- (Particularly during cold months when students may experience seasonal affective disorder)

Address past experiences.

If your school has a counselor who utilizes trauma-informed techniques, this can help students whose past experiences might be affecting their motivation. Make sure students are aware that this resource exists, and maybe bring the counselor in so they can introduce themself and explain their job.

Teachers can also educate themselves on trauma and become more aware of the signs. If you suspect that one of your students needs support, set up an informal meeting (you don’t want the student to feel bombarded) to connect.

Let your students know that you’re available to chat about their lives and that they can set up meetings with you outside of class (if your schedule allows for it).

Final thoughts

Expecting students to achieve highly in school (and beyond) without creating a space that fosters motivation is like trying to successfully run a 5k after going to an all-you-can-eat Indian food buffet. It simply won’t turn out well!

Undeniably, motivation is a huge part of students’ success in school. It’s thus of the utmost importance for teachers to nurture student motivation in the classroom.