A few months ago, I watched Kelly McGonigal’s Ted Talk on stress. Even though I was actually seeking information on procrastination, McGonigal’s talk opened a door for me, changing my entire perspective on stress.

In McGonigal’s talk, she explains that, with so many of her patients, she’s demonized stress. That is, she’s promoted the common notion that stress is the enemy.

For a while, she’d been making it her number one priority to help her patients eliminate stress entirely from their lives.

But years later, she realized this was a critical mistake. Because in reality, stress isn’t innately bad. It’s merely the body’s natural reaction to certain demands and forms of stimulation.

It can be harmful, McGonigal notes — that is, chronic, high stress is damaging. But what so many of us are dealing with (low-to-moderate levels) is a different story.

As of recently, research has shown that low-to-moderate stress is usually only harmful to us when we perceive it to be harmful (in the sense that it causes significant, short- or long-term damage).

I realized that, like so many people I know (and like McGonigal), I had made stress into the ultimate enemy!

All over the internet, students can find articles, videos, and blogs about why stress is going to cause their downfall and how it can lead to any particular symptom.

Why is it that we’ve decided that, unequivocally, stress is bad?

Binary thinking: a human tendency

As humans, we often think in dichotomous ways. (Perhaps that’s partially why the phrase “It’s not black and white” exists? Because so often we assume that it is black and white?)

In so many situations, we categorize items on a binary spectrum (this or that). We’ve got perfect vs. imperfect, right vs. wrong, good vs. bad, normal vs. abnormal, rich vs. poor, smart vs. dumb, pretty vs. ugly, healthy vs. unhealthy, etc. The list goes on.

We do this because it’s simply easier to concretely categorize something than to try and understand its more complex nature. And in almost all of these categories above, we’ve identified, to some extent at least, good vs. bad.

This is a cognitive shortcut, and evidently so pervasive, that in psychology, it’s got its own defined term (the Binary Bias).

As much as we’d like to think that we’re able to look at all sides of a situation, when it comes down to it, it’s much easier to just stick a label on a situation, news, event, or someone’s behavior. It’s either good or bad.

In an interview, psychologist Andre Hartz describes this way of thinking as “splitting,” and something we do because we have trouble sitting with ambivalence — “which in psychology refers to the experience of having conflicting emotions toward the same thing at the same time — for example, acknowledging that we have both strengths and weaknesses.”

With stress, perhaps it’s a lot easier to categorize the feeling as bad rather than to try and understand its more complex nature — and to recognize that it can be bad and good.

Simplification and sensationalism

Another way in which we (often inadvertently) simplify things is by assuming that any particular situation or event is dramatically good or dramatically bad. That is, when we see overdramatic information, we’re more likely to hold onto and remember that.

When it comes to stress, you’ll see headlines such as, “Stress: the Ultimate Ager.” This not only misleads us, but also likely causes us more stress than we had in the first place!

In the media, recognizing and acting on our affinity for the dramatic is a tactic called sensationalism. Essentially, journalists will use shocking words, exaggeration, or even lies to attract attention. Due to this extremism, we actually have to seek out the more ordinary, middle ground (so to speak) news.

Furthermore, this is one of the reasons why we’ve developed this misconception around stress.

Stress: Good or bad? Or both?

Since the dawn of time, we’ve responded to threats with the fight or flight response. This is the body’s immediate response to a perceived threat. And it evolved as a survival mechanism, because it allowed us to quickly react in dangerous situations (either fight off the threat, or flee from it).

Fight or flight is related to stress — as you may know, we tend to perceive stress as a threat, whether or not it’s actually life-threatening. (If you think about the stressors in your life, you can probably conclude that usually, they’re not life threatening.)

Think about it. Consider what you stress about. Here are some common situations:

- College admission interviews

- Starting a new job

- A confrontation with a teacher/boss/friend/significant other

- An important public appearance/sporting event/performance

These situations are often not life-threatening, though they may certainly feel that way in the moment. But even though, unlike some of our dear ancestors, we’re not faced with escaping saber-toothed tigers, so many of us, when we feel stress, respond (physiologically and emotionally) as if it is a true threat.

Mindset matters

Ralph Waldo Emerson said, “Once you make a decision, the universe conspires to make it happen.”

No, we can’t just decide what we want, snap our fingers, and have it appear. But, Emerson was onto something.

For many of us, the idea that your attitude can significantly impact an outcome can seem mind-boggling. But research continually suggests that the mind can truly do wonders.

In a 2007 Harvard study, psychologist Ellen Langer highlighted how the mind can do wonders. Langer conducted a study that included 88 hotel maids. She told half of the maids that their jobs included intense exercise. She then gave them information about how their daily tasks boosted their fitness. Meanwhile, Langer didn’t tell the other half of the maids anything.

After just one month, Langer discovered that the maids who believed their work involved serious exercise had lost weight, lowered their blood pressure, and developed a healthier body composition. (The maids reported no changes to diet or daily routine!) On the flip-side, the other maids reaped none of these benefits.

In a 2011 study, researchers gave half of the participants what they called a hefty, high calorie milkshake. Meanwhile, they told the other half that they were drinking a lean, low calorie milkshake. Although all participants had identical milkshakes, those who perceived the treat to be indulgent had greater measures of satiety (feeling “full”).

Recently, research has found that people who have a positive outlook on aging tend to live longer than those who have a negative outlook on aging.

All of the research above tells us that our mind can play tricks on us — in an awesome way — and affect our outcomes. And once we understand this, we can be more aware and leverage our mindset to help us achieve our goals.

Perception of stress is everything

Despite what many students have been led to believe, research has found that our perception of stress, rather than the stress itself, is what’s actually harmful.

In a study of more than 180 million adults, participants who perceived that stress affects their health had an increased risk of premature death compared to those who didn’t perceive that stress affects their health.

Similarly, a review of three studies found that those who viewed stress as debilitating tend to over- or underreact to stress (which can lead to worse health outcomes).

Meanwhile, the review also showed that those who believed stress to be beneficial are less affected and are also more likely to seek and be open to receiving feedback during stressful times (all of which is helpful for long-term growth).

Just off the bat, this, again, tells us that mindset matters.

But if you’re still not convinced, consider this:

Beyond debunking the common notion that stress is innately harmful, research has also found that low-to-moderate levels can actually be beneficial!

The benefits of stress

1. Stress can boost cognitive performance.

Students know stress. Before exams and presentations, it’s common for students to experience stress. Will they be able to execute as well as they want to?

Meanwhile, so many health and wellness platforms articulate that any stress is downright bad. And they promote ways for students to eliminate their stress. But more and more, research is finding that some amount of stress actually can boost students’ performance.

For instance, one study found that low to moderate levels of perceived stress were linked to improved memory and as a result, elevated “mental performance.”

Another study from the University of California, Berkeley found that acute stress can actually create new brain nerve cells. In turn, this can improve cognitive and mental processes. According to the researchers, having a low-to-moderate amount of stress can help improve:

A recent study confirmed that stress can, in fact, boost things like cognitive performance.

The researchers taught participants (adolescents and young adults) how to reappraise their stress. (Stress reappraisal refers to reframing how one thinks about stress. In this case, the participants were taught to think about how stress can benefit cognitive performance.)

The researchers found that this reappraisal method helped participants:

- Reduce their anxiety

- Achieve higher scores on tests

- Procrastinate less

- Stay enrolled in class

Learning the stress reappraisal method can be extremely beneficial to students, who have regular exams and assignments to complete, and who sometimes struggle with test anxiety.

2. Stress can also boost the immune system.

Meanwhile, stress can also benefit students by boosting their immune system. And there’s a direct relationship between the immune system and academic performance.

For instance, a 2012 Stanford University School of Medicine study found that short-term stress heightened the immune system among rats.

The scientists determined that, while long-term chronic stress is often harmful, short-term stress can stimulate our fight-or-flight response. Then, we experience what we know as stress, and in turn, our body produces cortisol. In turn, this short-term stress indirectly boosts our immune system.

Another study, published in the Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, found that having short-term stress before surgery actually helped speed up recovery, compared to people who had no stress before surgery.

A third study found that manageable stress can improve resistance to certain diseases and conditions.

With a moderate amount of stress, students may actually improve their immune system. And the result here is simple. With better health, students will show up better equipped to succeed in school. They’re more likely to take in more information and ultimately do better on their exams.

3. Stress leads us to reach out to others

Think about a time in your life when you experienced stress.

Maybe you were thinking about an upcoming one-on-one meeting with your boss or your teacher. Maybe you had a big move coming up. Or a big soccer game.

Whatever the case was, did you feel like you wanted to sit with it alone, or were you wanting to share your stress with someone in your life?

For many of us, the latter is often the case.

And in fact, as research shows, we tend to reach out to others for support in times of stress. One of the main reasons for this is that when we experience stress, we release oxytocin, a hormone that promotes feelings of bonding and connectedness.

For students (and quite frankly, for all of us), maintaining social connectedness helps elevate both emotional and physical health — both of which are related to better academic performance.

Indeed, as research shows, a sense of belonging is directly linked to improved academic outcomes.

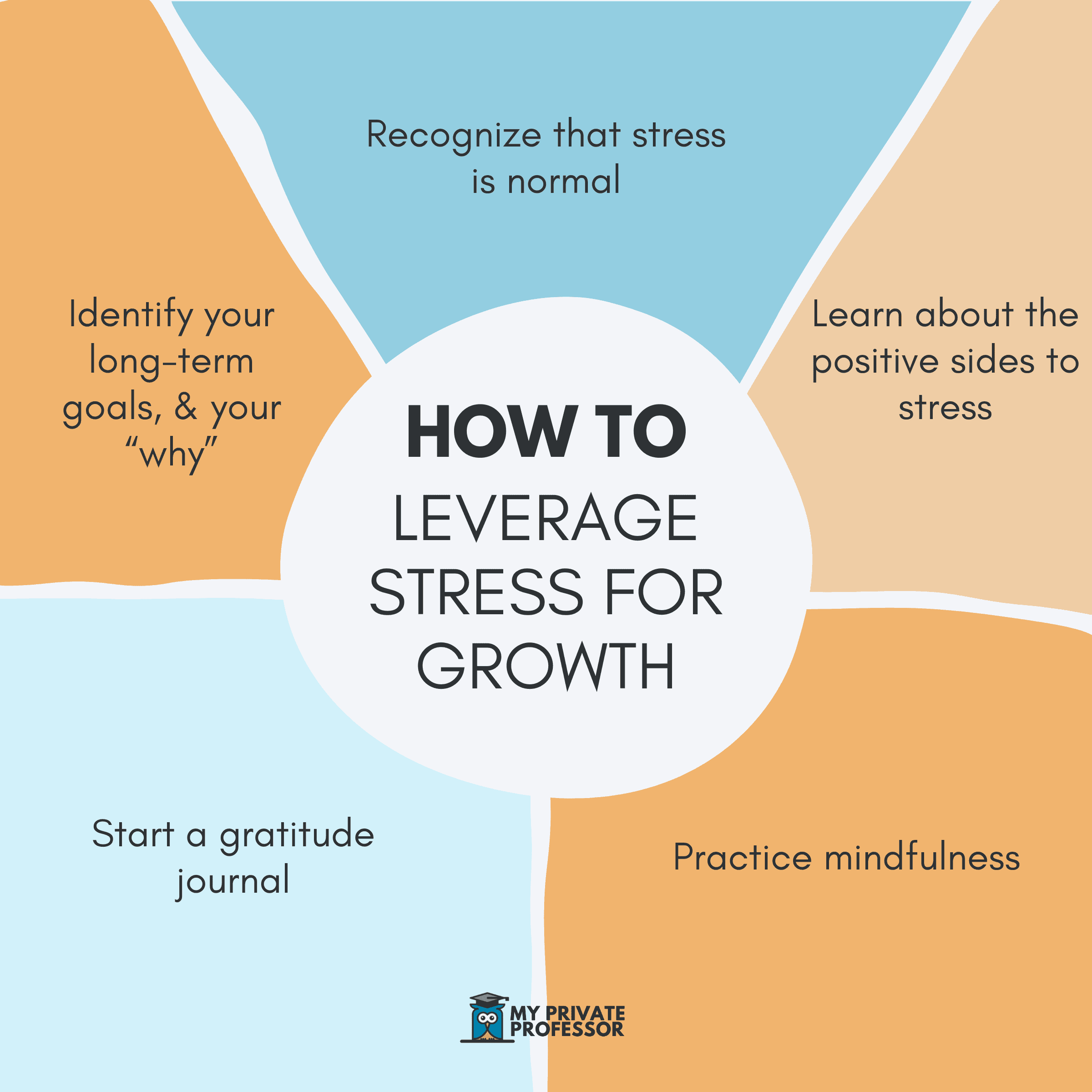

How to reframe your perspective on stress

The first thing to do when changing your mindset around stress is to remember that it’s completely normal to experience stress, and usually expected!

It’s also imperative to acknowledge that, with the help of several external sources, you’ve constructed this notion that stress is inherently and automatically bad.

Realize that while stress can cause feelings of discomfort, it often has benefits for you over the long haul. That is, stress can help prepare your body to act and motivate you to continue working for, and ultimately achieve, your goals.

In fact, research shows that when you experience stress, your brain releases dopamine. And one of the results here is that you’re more motivated to take charge.

Something else you can do is reframe the stress trigger when it happens. If you view stressful events as challenges that can help you grow rather than threats, you’ll be better able to channel your strength and energy towards overcoming the event instead of letting your fear drive you to flee.

For instance, if you’re someone who experiences test anxiety, you can try to change your mindset on these pre-exam jitters. Instead of seeing them as threatening, try imagining that these feelings are actually giving you a headstart into your test, pushing all of your hard work into action.

The Journal of Individual Differences, indeed, found that those who chose to view stressful events as challenges instead of threats had less emotional exhaustion during stressful events.

And the last thing to remember is that you learn by doing — life is one big trial by error. Likewise, stress reappraisal is a journey and it’s okay if it’s a bumpy road at first.

Final thoughts

Have a slight cough? Or a sore back? Or a little itch on your pinky toe? It could be because of stress, we’re told.

Because we’ve demonized stress so much, students are often quick to believe these claims.

But a lot of the time the claims in the headlines are fully misleading! Take, for example, this recent U.S. News & World Report headline: “5 Surprising Ways Stress Can Lead to Weight Gain.”

This headline strengthens the negative associations we already have around stress. And it pairs two things together, both of which we are conditioned to think of in a negative light. But in the actual meat of the article, the authors are only talking about chronic stress.

As mentioned, research has actually debunked the idea that stress is innately harmful. By using the general term “stress,” this article paints a deceiving, overgeneralized picture of how stress can impact health.

At the end of the day, it’s impossible to completely eradicate stress from your life — and, turns out, that’s not entirely a bad thing.

Once you can recognize and then accept that you can’t fully eliminate it, you’ll liberate yourself from feeling like you must work your hardest to not ever be stressed. Because really, stress is a natural, human response.

By taking the reins and shifting your perspective, you can change your outcomes. Remember: your stress-induced feelings are a product of your mind, not the other way around. Basically, you run the show!